“Raoul Wallenberg – Report of the Swedish-Russian Commission”

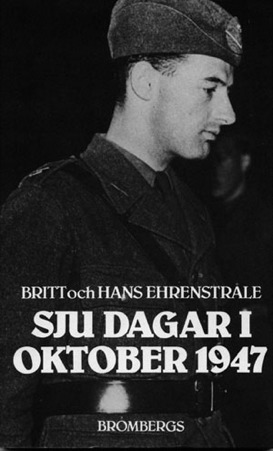

It was in 1947 that Hans and Lillan became involved with the search for their missing compatriot. They both served in Poland, Hans as head of the Swedish Relief and Reconstruction Mission and Lillan working with the Swedish Save the Children Fund. In October that year they were approached by the Swedish and American Embassies respectively, independently of each other, to go to Southern Poland to locate and bring back a group of escaped Soviet prisoners, one believed to be Raoul Wallenberg. The wounded men were believed to be prisoners from the Soviet Union travelling on a train which had been ambushed near Przemyssle on the Polish Soviet border.

They pursued each their own lines of investigation, and it was Lillan who, through Partisan contacts happened to locate the wounded men. She was taken to a barn in the forest clearing about 15 km east of Tarnow where she handed over U$5000 to the Partisan leader which had been given to her by the Americans. Then she was shown three desperately wounded and dying men. She recognised one of them as Raoul Wallenberg whom she had met in Sweden shortly before the war. When she knelt beside him she smelt the stench of gangrene. She whispered to him in Swedish “are you Raoul Wallenberg, then press my hand” She felt a light response from him. There was no way she could remove him, especially since the Partisans refused. She was brought back to the little church from where she had been driven on a motorbike to the barn. She spoke to the priest about taking care of the wounded and their eventual burial in the churchyard.

Their joint but of each other independent expeditions to the forest region of Southern Poland had been fraught with danger. When they were back in Warszaw they reported, Hans to the Swedish Ambassador and Lillan to the American official, a friend of hers. The further developments of their involvement in the search for a missing compatriot became more and more complicated and confusing. Lillan was sent to Stockholm to report to the Chairman of the Swedish Raoul Wallenberg Committee where the reception was rather hostile and branded as “…misleading to draw attention away from the USSR”.

She returned to Warszaw and when met at the airport by Hans she burst out in a sad “ We must forget what we have done. They said we are in collusion with the Russians”.

It is not easy to forget an experience of such political and human dimensions. But Hans and Lillan tried to keep their “adventure” for themselves. They had no need for publicity, on the contrary, they feared that their involvement could harm their future prospects of work. Now and then, nolens volens, they were reminded of what they had been mixed up with during seven eventful days in October 1947. They kept away from related publicity even when a Readers Digest-type of article appeared in the 1950s giving an alarmingly detailed account of their expedition to South Poland. Although the story was full of genuine details the most important part – Lillans’ encounter with the wounded men in the barn – were missing. Hans and Lillan did not move but remained silent, confident as they were that this was fully covered in their own verbal report to the Swedish Ambassador Westring in Warszaw who in turn reported via radio as well as by hand to the Foreign Office in Stockholm. Mr Westring’s report was on the top secret Raoul Wallenberg archives from where it in due course would be released in the future…